Trade, Migration, and Productivity in China

What’s Up In Economics

By Joe Maginnis

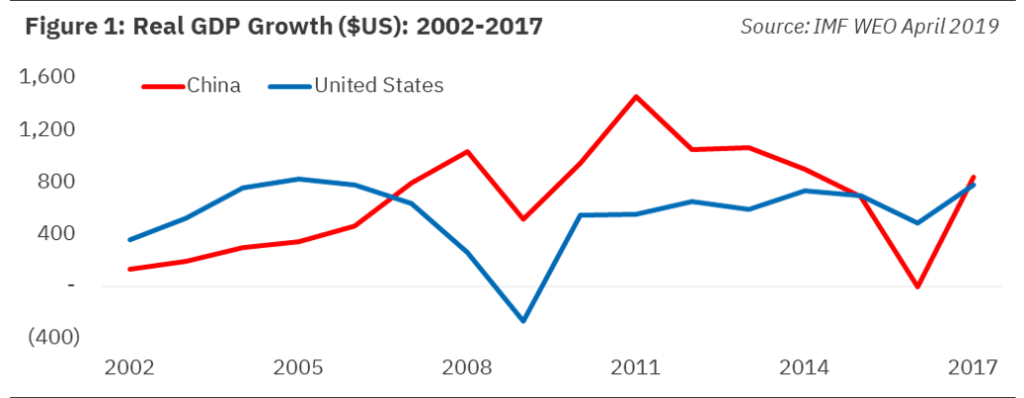

It is well-known that China’s economy has experienced unprecedented growth in the 21st century. For reference, China’s GDP per capita increased from $1,149 in 2002 to $8,827 in 2017 – an eightfold increase in just 15 years. Over that same period, China accounted for 23% of global economic growth, while the U.S., the world’s largest economy, only accounted for 19% of global growth (figure 1). China’s rapid economic expansion beginning in the early 21st century is commonly attributed to the relaxation of its external trade policies (meaning trade with other countries). In this month’s article, two Canadian economics researchers, Trevor Tombe and Xiaodong Zhu, find evidence from several Chinese data sources that a greater portion this growth was due to its internal trade and migration policies, which affect how workers and goods flow within and between provinces.

Before the 21st century, China’s trade and migration costs were exceptionally high. External trade barriers existed in the form on non-compliance with World Trade Organization (WTO) standards, while internal trade costs were imposed by provincial government protectionism and lack of good infrastructure for transportation. Similar policy and infrastructure issues crippled labor mobility within and between provinces, with the primary culprit being the hukou system (China’s household registration system). China had laws that imposed high costs on laborers working outside their hukou, primarily in the form of restricted access to social services and employment rights, which, according to the researchers, were high enough to shrink a migrant workers’ real income by a factor of three.

China’s accession into the WTO in 2001 made waves in the world economy. Less known, however, are the major policy reforms and infrastructure investments that drastically reduced internal trade and migration costs and boosted productivity at around the same time period. Various State-Owned Enterprise reforms in the early 2000s reduced the size of local government, thereby reducing their incentive to engage in local market protections. Spurred by demand for migrant workers in manufacturing, construction, and labor-intensive service industries, many provinces eliminated the requirement of temporary residence permit for migrant workers after 2003. And heavy investment into transportation infrastructure further reduced trade and migrations costs. The researchers’ findings suggest these internal policy and infrastructure changes accounted for 28% of labor productivity growth between 2000 and 2005, compared to only an 8% effect for external trade policy changes. These findings emphasize the importance of labor mobility and trade on labor productivity in an economy.