Public Debt and Low Interest Rates

What’s Up in Economics

By Joe Maginnis

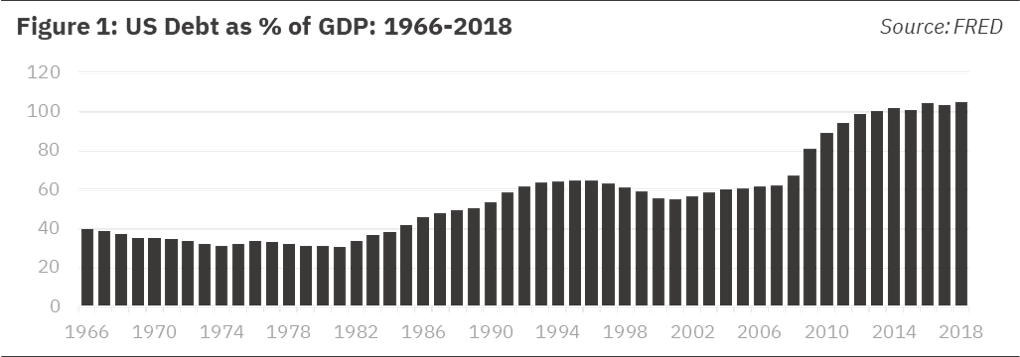

The lecture by Oliver Blanchard offers a unique perspective on the fiscal and welfare implications of high public debt. Popular opinion on public debt is one of concern. The current debt to GDP ratio is near its all-time high, which increases the perceived risk of borrowing from the US in the eyes of investors. In the event of economic uncertainty – something that is looming as we approach the end of the business cycle – borrowers of US currency will demand higher interest rates, which may hinder the US’ ability to roll over its debt obligations if GDP growth cannot keep up with interest rates. This perspective about public debt urges officials to engage in contractionary fiscal policies to lower the public debt to GPD ratio, or least prevent its continued growth.

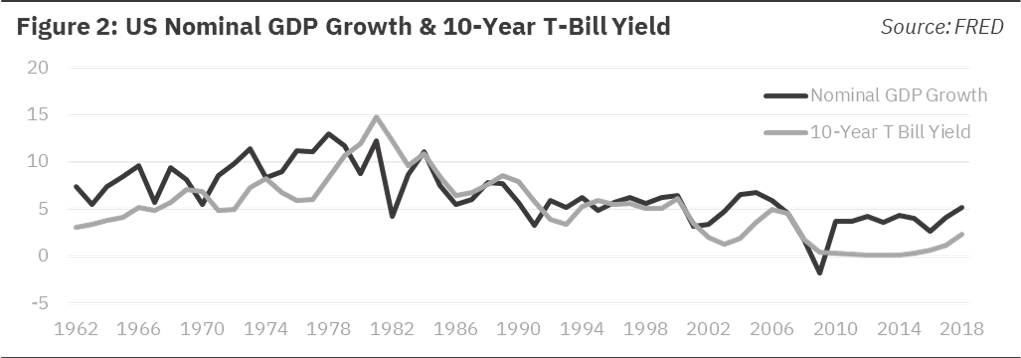

The author understands the concerns about high public debt mentioned above, but he also points out that the argument above does not have straightforward implications for the appropriate levels of public debt – it merely says that debt levels are too high – so the author attempts to bring other perspectives about public debt to light. The main claim the author makes is that nominal GDP growth has historically been higher than riskless interest rates, which indicates that, over the long term, the US can issue new debt without raising taxes if historical dynamics between interest rates and GDP growth continue into the future.

After pointing out that nominal growth has been historically higher than riskless interest rates, the author opens up a dialogue about the factors that matter for optimizing the levels of public debt. First is the welfare cost of reduced capital accumulation due to the higher taxes needed to fund interest payments. The author shows that the welfare cost above may be smaller than typically assumed because 1) the risk-adjusted return to capital is low (shown in figure 2), and 2) the average risky rate may be lower than what is measured by the public market. The author defends his second claim by showing that, even though earnings growth has been solid among US corporations, fair asset values have remained relatively low. That means 1 of 2 things could be happening: either fair values are being improperly measured, or US companies are receiving higher rents as a proportion of their total income – implying the marginal product of capital is actually lower than what is measured. This matters for debt because a lower marginal product of capital means a lower welfare cost associated with high public debt. The lower the welfare costs of public debt, the higher the optimal level of public debt. The author ends by insisting that we need to gather more information about the welfare costs of public debt before we make decisions about how to proceed.